The LaRouche organization’s 1983 scheme for winning Spain’s «dirty war» against Basque nationalists:

BRING BACK FRANCO’S TORTURERS

(and persuade the French police to cooperate…)

Herbert Quinde, a top operative for U.S. ultra-right ideologue Lyndon LaRouche, was pleased when, in 1983, Spain’s new Socialist government appointed one Manuel Ballesteros–a police official who had tracked communists during the Franco era and then transitioned seamlessly into tracking terrorists on behalf of the post-Franco democracy–to advise on the struggle against the Basque separatist organization ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna – The Basque Country and Freedom).

Spanish police torturer and death squad protector Manuel Ballesteros, 1935-2008.

Quinde wrote in LaRouche’s Executive Intelligence Review (Dec. 13, 1983):

«Interior Minister Jose Barrionuevo has attempted to balance all these contending influences [between the «hard line,» which Quinde supported, and a supposed British-Israeli «technocrat» line–DW] by creating the Consejo Superior para la Informacion, a national advisory board on security policy. Although the Consejo will not get off the ground before the beginning of next year, the return of Manuel Ballesteros, former director of the Mando Unico Lucha Contraterrorist [sic] (MULC) to an advisory role in security policy indicates that the partisan politics in the intelligence community which weakened the government’s counterterror policy, may be nearing an end.»

But Quinde neglected to mention one very important fact: that Ballesteros was among the most notorious police torturers of the late Franco years, and also of the transition period after Franco’s death and the years of the Union of the Democratic Centre (UCD) government that won the 1977 elections–Spain’s first democratic elections since the 1930s. Quinde also failed to inform his readers about the 1981 torture-murder of alleged ETA member José Arregui, conducted under Ballesteros’ supervision, that had triggered a general strike in the Basque Country, a protest rally of tens of thousands of Basques, the arrest of several police officers and the resignation of National Police Director José Manuel Blanco, as well as the temporary stepping-down of Ballesteros himself.

Quinde apparently saw the return of Ballesteros as a sign that the «dirty war» was going to be waged with greater ruthlessness. The LaRouche aide would have viewed this development favorably because he and his boss had been pressing the Socialist government’s Interior Ministry and security police (see details below) to adopt the same tactics against ETA that Ballesteros and his colleagues had used during previous years.

Indeed, at the time Quinde wrote his article (and as he well knew from his meetings with Spanish police officials), a new wave of Socialist-approved repression was already underway involving a network of Spanish police officers and neo-fascist mercenaries known as the Grupos Antiterroristas de Liberación (Antiterrorist Liberation Groups), or GAL. The GAL would kill 27 people between 1983 and 1987–at least a third of them having no known connection to the ETA or any other terrorist group. The forays of GAL, such as the aptly named Operation Mengele, would result not only in deaths and other casualties from bombings and shootings but also in kidnappings and torture-murders.[FN 1]

Ballesteros’ background

Ballesteros was born near Granada in 1935, one year before the start of the military uprising that brought on the Spanish Civil War and resulted in the 36-year fascist dictatorship of «Generalissimo» Francisco Franco. Ballesteros obtained a university degree in criminology and then began his professional career in Franco’s police under the tutelage of Roberto Conesa Escudero, the monster who served as Franco’s chief torturer.[FN 2]

Ballesteros joined the Social-Political Brigade, which was dedicated to hunting down communists, union activists, Basque and Catalan nationalists, and anyone else interested in ending the dictatorship. He would then head up the police department in Valencia, where he primarily targeted communists, before shifting his focus to the Basque region–first to San Sebastián and then to Bilbao–when the ETA escalated its armed struggle in the mid-1970s.

Using the «toaster» on a captured communist

On November 11th, 1968 in Valencia, Ballesteros and men under his command arrested 36 members of the Comisiones Obreras (Workers Commissions) who were found to possess copies of the outlawed Communist Party’s newspaper. Interrogations of these captives under torture led to the arrest of local Communist leader Antonio Palomares.

Antonio Palomares, 1930-2007.

Ballesteros and his team brutally tortured Palomares. Among the techniques used was the «toaster,» which consists of the victim being tied down on bedsprings that are connected to electrical currents. In spite of repeated sessions on the toaster, Palomares held out and did not give up any names of his comrades. However, he left police custody with a broken body. Three of his vertebrae were fused together, his diaphragm was damaged and his breathing was permanently affected. He was two centimeters shorter than when he was first arrested. A photo of his beaten face was released and it forced the authorities to temporarily remove Ballesteros from his position. Despite this minor setback, however, his reputation as an «expert» in interrogation tactics grew.

Franco died in 1975, but fascist elements remained strong in the police and military–and were determined to halt the democratization process. It is thus not surprising that Ballesteros–promoted to head the Central Intelligence Brigade (Brigada Central de Información) of the Spanish security forces in 1976–continued to violate human rights with impunity.

A key aspect of his work during the years of the UCD government (1977-1982) was facilitating the activities of the anti-ETA death squads known collectively as the Spanish Basque Battalion (Batallón Vasco Español, or BVE). Although the public outcry over the murder of José Arregui caused the torturer-in-chief to tender his resignation, he was brought back within weeks to head the newly formed Mando Único para la Lucha Contraterrorista (Unified Counterterrorist Command), or MULC.

The ETA refused to lay down its arms when the democratization process began–national self-determination was the insurgent group’s aim, not just the end of Spanish fascism. The violence grew in intensity, and the new government turned to the likes of Ballesteros–hard men with many years of experience in tactics of political repression–to wage la guerra sucia (the «dirty war») against the ETA. Their first post-Franco death squad operation–the BVE–would kill at least 20 people between 1977 and 1981. Several of the victims were unconnected to terrorist activity; for instance, the gypsy child and her pregnant sister who were killed by a bomb placed indiscriminately outside a playschool.[FN 3].

The BVE’s most widely publicized action was against ETA militant José Miguel Beñaran Ordeñana, a/k.a «Argala.» He had been a member of the unit that assassinated Franco’s prime minister and hand-picked fascist successor, Admiral Luis Carrero Blanco, by blowing up his car in 1973 when he was preparing a new crackdown in the Basque Country. The assassination was widely applauded at the time by opponents of the dictatorship, both Spanish and Basque.[FN 4]

On December 21, 1978, Argala was blown up by a car bomb planted by Spanish security agents with the help of members of the Spanish Navy and, according to one of the participants, using explosives obtained from a U.S. military base in Spain. The bombing was planned to take place on the fifth anniversary of the fascist Admiral’s death, but was not carried out until the following day because Argala did not leave his house on the desired date.

Argala was definitely still an active combatant against the Spanish state at the time of his death, but the point here is that the Navy and the police felt entitled to take vengeance against him for an action undertaken against the fascist regime of Franco–i.e., to act as if that regime were still in power–even though the Franco era police and military had been granted a blanket amnesty (Law 46/1977) for crimes vastly greater than any that had been, or would be, committed by ETA.

Ballesteros and cross-border murders in France

Two years later, on Nov. 23, 1980, a pair of armed men walked into the Bar Hendayais in the northern Basque town of Hendaye, in France. They opened fire that Sunday evening on everyone inside the bar. Two men without any known political affiliations were murdered in the attack–José Camio, a local worker, and Jean Pierre Aramendi, a retiree. Another 10 people were wounded, including Jean Louis Huber, who received a shotgun blast to the stomach and has undergone dozens of surgical operations since that night.

The gunmen then rushed out to a green Renault 18 where their driver was waiting. With French police in pursuit, they were able to cross the border into Spain before they crashed their car. Irish journalist Paddy Woodworth describes the outcome in Dirty War, Clean Hands (2001):

«Surrounded by armed police and guardias civiles, three men emerged with their hands up. One of them was brandishing a Madrid phone number and claimed they were doing a job for the Spanish police. While some of the police were finding a rifle, four pistols and magazines in the Renault, another policeman was helpfully calling Madrid. The number turned out to be that of Manuel Ballesteros, head of police intelligence and director of the newly established Unified Counter-terrorist Command….Ballesteros was regarded as the force’s leading expert on ETA, and had served as a police chief in Bilbao and San Sebastián.

«His instructions were succinct: ‘Let the matter drop. No one has seen or heard anything.’ Despite the vociferous protests of the French police, just a few yards away, the men were driven away into the obscurity from whence they had come. They have never been officially named, or charged. Officially, in fact, they have never been seen again.»[FN 5]

Ballesteros was convicted twice of failing to cooperate with the justice system in the Bar Hendayais case (among other things, he refused to provide the names of the two gunmen and ignored summonses). Yet both times he managed to evade punishment even though he had never denied his complicity. The first conviction, in a Spanish court, was overturned by a higher court. The second conviction, in a Basque Court, resulted in three years of professional disqualification from police service and a fine of 100,000 pesetas (a remarkably light sentence for conspiring to cover up a double homicide), However, even this slap on the wrist was vacated by the Spanish Supreme Court, which ruled that the Basque court in San Sebastián lacked jurisdiction.

Nine days of torture

Madrid’s Puerta del Sol is currently (2011) the epicenter of the anti-government demonstrations by «los indignados» who gather and camp out there to protest government corruption and the lack of jobs. But 30 years ago, the old Post Office facing the plaza was used by Ballesteros and police under his command to torture anti-government militants. Indeed, ETA member José Arregui was tortured there in 1981 for nine consecutive days before being sent to the Carabanchel prison where he died from the effects of the torture.

The old Post Office facing on the Puerto del Sol in Madrid. Thirty years ago, Ballesteros used it for torturing Basques.

Arregui was arrested in Madrid on Feb. 4 of that year, along with fellow Basque militant Isidro Etxabe. On Feb. 14, he died in the Carabanchel prison hospital of a «heart attack,» according to the official version of his death. He was given a closed casket funeral and buried on Feb. 16. Several individuals who doubted the official story of his death went into the cemetery and dug up his body in order to photograph the damage that had been done to him. The images were horrifying, and, as noted above, triggered massive outrage and protest actions in the Basque Country.

The Spanish Human Rights Association (APDHE) reported that no less than 73 police officers under Manuel Ballesteros had been complicit in Arregui’s torture. The techniques used seem to have been motivated more by sadism than by any desire to get information out of him. He was beaten over his entire body. His feet were given the treatment called «la barra» (the bar) where the victim’s hands and feet are tied or cuffed together over a steel bar. The soles of the victim’s feet are then beaten, causing severe bruising and, in many cases, blisters that form and then burst–over and over again–from the repeated blows. Arregui’s feet were so blackened that some believe that they were also burned in some way, although other victims of that form of torture say that the blackness is caused by the beatings and ruptured blisters.

La bañera (the «bathtub»)

Arregui also had to suffer Spain’s version of waterboarding, called «la bañera» (the bathtub). The detainee’s head is forced down into a washtub filled with water in order to make him or her experience the sensation of drowning. Many times the tubs are not only filled with water but also with feces, urine and the victim’s own vomit. Significantly, an autopsy report that came out after the publication of the photos said that Arregui’s death was the result of «respiratory failure caused by bronchopneumonic process with intense bilateral pulmonary edema and pleural effusion in both chambers and pericardium.» It has been suggested that the lung condition was the result of his torturers flooding his lungs with filthy water and that his immune system had been weakened by the beatings and other mistreatment to the point that this previously healthy 30-year-old truck driver could not fight off the infection that killed him.

Other prisoners in the Carabanchel prison gave personal testimony about the terrible condition that Arregui was in from the interrogation sessions, and also revealed statements he had made to them about how he’d been tortured. His death triggered a hunger strike by over 100 Basque prisoners at Carabanchel as well as the protests throughout the Basque Country.

Ballesteros victim José Arregui. His torture-murder was widely publicized in the media, and triggered mass protests in the Basque Country.

The progressive Spanish police union, the USP (Unión Sindical de Policía), issued an «unequivocal condemnation» of what it called an «unspeakable act,» and demanded Ballesteros’ dismissal. In reply, Ballesteros called the USP a «tiny, sectarian group» with «no moral and professional authority» to request his dismissal. Its criticisms, he added, would not in the least affect his «dignity as a person and policeman.»

Of the 73 policemen alleged to have taken part in the torture of Arregui, only two were ever charged with the crime. They were found not guilty at their first trial. A later trial found them guilty and sentenced them to seven months in prison, but they had already received so many decorations, awards and promotions that the sentence was almost meaningless. Manuel Ballesteros was never prosecuted for his role in the death of Arregui.

When the Socialists took power in December 1982, it seemed at first that Ballesteros would be kept at arm’s length, and that the BVE, which had ceased to conduct any operations by the middle of 1981, would be the last of the death squads. But after the ETA failed to halt its terror attacks, the police along with the Interior Ministry of the Socialist government resolved to form a new death-squad network, this time under the GAL label. And the new Interior Minister, José Barrionuevo–a former leader of the Falange’s Union of Spanish Students (Sindicato Español Universitario, or SEU)[FN 6]–soon put Ballesteros back to work as an anti-terrorist adviser, and would send him to Algeria in 1987 as the lead negotiator in informal exploratory talks with ETA leaders. These sessions, in which the government was also represented on at least one occasion by state security director Rafael Vera and police intelligence chief Jesús Martínez Torres (both of whom had been involved with the GAL), would ultimately prove fruitless.

Herb Quinde and the GAL death squads

Herbert Quinde played a significant role in the creation of the BVE’s successor–the GAL–according to former Spanish security officials. They say he provided international contacts, especially in France, that would be vital to the operational effectiveness of the new units. Quinde–who operated out of LaRouche’s Wiesbaden, Germany intelligence office (which was under the protection of the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, West Germany’s domestic intelligence agency)–met on at least a half dozen occasions with Spanish officials who were planning a new campaign against ETA. On more than one visit, Quinde was accompanied by a high-level officer of the French Gendarmerie who turned over to his Spanish counterparts abundant documentation on ETA members living in France.

Quinde’s earliest trips to meet with Inspector Mariano Baniandrés and other security officials had left them dubious of his motives–and Quinde didn’t help matters when he made a strange offer to trade his information on ETA for a dossier on the business holdings of the family of the late Otto Skorzeny, Hitler’s favorite Commando, who had been given refuge by Franco following World War II. [FN 7]

Baniandrés and his associates decided to play if safe, and arranged for round-the-clock surveillance of Quinde during a subsequent visit he made to Madrid. However, the photos and addresses of purported ETA members living in France that Quinde and his companion proferred went a long way towards allaying Spanish suspicions.

According to an August 1995 article in the Madrid daily El Mundo co-authored by Antonio Rubio, Manuel Cerdán and this author:

«Police sources who participated in the events mentioned above, confirmed all of this to El Mundo. Near the end of 1982, shortly before the October elections won by the Socialist Party, LaRouche visited Madrid for a meeting with Baniandrés. A police commissioner who knew the ultraright leader put them in contact. LaRouche stayed at the Hotel Palace, protected by bodyguards armed with machine guns. It was there that he received the Spanish agents.

«After this encounter, Baniandrés met with LaRouche’s right-hand man, Herbert Quinde. He [Quinde] travelled from Germany where he edited an intelligence magazine. The encounters between Baniandrés and Quinde were repeated on various occasions.

«On the third or fourth visit, Quinde offered to serve as a bridge with the French police for collaboration in the fight against terrorism. Baniandrés, who had by now been named head of the Interior Brigade, organized a meeting with French police at which Jesús Martínez Torres, Commissioner General of Information, Pérez Corredera and José María Escudero were present. For the French, a Lieutenant Colonel who served as the right-hand man for General Pidou, head of the Gendarmerie, traveled from Paris.

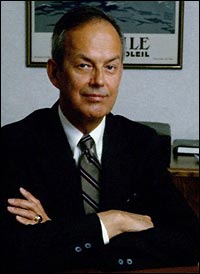

Herbert Quinde circa 1978. This shadowy LaRouche operative traveled around Europe and Latin America in the 1980s cultivating death squad organizers and other far rightists. In 1983–according to authors Ricardo Arques and Melchor Miralles–he told the Spanish police he could help them find «professional killers» for their dirty war against ETA.«At the meeting they spoke about evening up the score with ETA by using its methods [i.e. terrorism], but finally reached an agreement by which the French government would deport ETA militants via emergency proceedings. This system was used later–in 1986–when Jacques Chirac became Prime Minister and Charles Pasqua was named as France’s Minister of the Interior.

«The French representative asked in return for Spanish collaboration in investigating a group of Corsicans who had sought refuge in the Basque country.

«The meeting was immortalized for posterity. From an ‘Apolo’ van, agents of the Interior Brigade photographed Quinde and the French official when they went to the La Barraca restaurant on the Gran Via.

«In July of 1983, Mariano Baniandrés was removed from his job and from the meetings. Police officer Alberto Elías was put in charge of the matter and continued the meetings with LaRouche and Quinde. Months later, the GAL were born with the collaboration of foreign mercenaries and French police.»

The individuals whom Quinde met with in 1983 included two of the most sinister figures in the Spanish security bureaucracy. Martínez Torres was a Francoist know as the «torturer of Zaragoza» for his actions against communists in that city. After having facilitated the activities of the BVE, he replaced Ballesteros as head of police intelligence during the GAL years and shielded the perpetrators of GAL violence. José María Escudero, head of the Central Intelligence Squad, was a protégé of top torturer Robert Conesa (see footnote 2); he worked against communists in the early 1970s and then was assigned to repression of anarchists. He had to resign from his supervisory position in 1986 after it was revealed that he had misidentified a target for repression (by circulating a picture of a terrorist’s brother rather than of the terrorist himself), although the daily El País suggested that the error was really the fault of Martínez Torres.

According to Ricardo Arques and Melchor Miralles, in Amedo: El Estado Contra ETA (Amedo: The State Against ETA, 1989), Martínez Torres and Escudero met with Quinde [the authors spell his name as «Kinde»] and the French official in March 1983 at the Central Intelligence Brigade’s headquarters on the Puerta del Sol (i.e., in the same building where José Arregui was tortured for nine days just two years earlier).

«During the meeting…there was discussion of the mistakes made by the BVE and an examination of the need to professionalize the ‘dirty war’ against ETA. Kinde promised to provide contacts with ‘professional killers.’ For his part the French official promised to contribute details, names, addresses, vehicles and schedules of ETA leaders living in France.

«A few days later, a high-level meeting took place in the Ministry of the Interior. In attendance were: General Casinello and Colonel Ostos, as representatives of the GAIOE [Gabinete de Información y Operaciones Especiales, or Intelligence and Special Operations Committee]; Rafael Vera, Sub-Secretary of State for Security; Jesus Martinez Torres, Inspector General for Information; and Francisco Alvarez Sanchez, the top police official of Bilbao. At this time it was decided to act against ETA in France. Immediately afterward, orders were issued to define and control as much as possible the participation of Spanish police officials in this work. It was necessary to maximize precautions to the utmost–to avoid old mistakes.»

It would appear that Quinde and his companion from France had influenced the plans of the Spanish police to a significant degree, and that the LaRouche organization itself, although lacking any real base in Spain, had gained a measure of credibility. An EIR team led by the chief of LaRouche’s European intelligence division would travel to Madrid the following month to meet with Interior Minister Barrionuevo (see sidebar).

But Quinde was not satisfied. In his Dec. 13 article–the one in which he praised the decision to bring back Ballesteros in an advisory role–he complained that the Spanish were not proceeding vigorously enough, even though the mayhem had already begun with the cross-border Lasa and Zabala kidnapping/torture/murder[FN 8] and the kidnapping of a French businessman who would be held and terrorized for over a week even though the GAL thugs knew they’d snatched the wrong man. But Quinde was thinking not only about counterterrorist violence but also about a broader type of crackdown–one right out of LaRouche’s neo-fascist playbook.

Quinde had scrutinized the Socialist government’s legal proposals for a state of siege in the Basque Country and apparently had noted just how well they fit with LaRouche’s political philosophy according to which it’s okay to outlaw criminal thoughts, not just criminal deeds:

«The most important [proposed legal] changes are the included harsh penalties for ‘apology for terrorism.’ With the intention of dismantling the political support network of ETA, the bill forbids any demonstration, public meeting, or press coverage giving ‘aid or comfort’ to terrorism. The new statutes also prohibit political associations that apologize for terrorism. This means that Herri Batasuna, ETA’s political party, may in the future be disbanded, and propaganda vehicles, such as the daily Egin and magazine Punto y Hora could be closed down.»

Ultimately, however, Felipe González’ government was unwilling to take a step so profoundly violative of civil liberties (even while it tortured and murdered its captured enemies), just as the British had hesitated to go quite that far in Northern Ireland in spite of using notoriously brutal tactics otherwise against the IRA. A full state of siege in the Basque Country would have to wait until a post-Socialist government came to power in 1996 (see footnote 9).

The killing and torture under the GAL brand name ended in 1987. But there had been so much ineptness–and so much gratuitous mayhem–that criminal prosecutions and media probes were inevitable. The public scandal and the prosecutions began in the late 1980s and picked up momentum during the following decade. When the full extent of the involvement of high-level police and government officials in the GAL conspiracy was finally revealed in the media, even Interior Minister Barrionuevo could not escape prosecution. Indeed, Prime Minister Felipe González (who almost certainly was involved in the conspiracy) and his Socialist Party would be voted out of power in 1996 in no small measure due to the GAL scandal.[FN 9]

José Barrionuevo (right)–a former Falangist student leader–was given the job of Interior Minister by the Socialists in order to placate hard-line police and military elements. He served in the post from 1982-1988 and would be indicted at the height of the public scandal over GAL. Convicted in 1998 along with state security director Rafael Vera (seated beside him) of ordering the cross-border kidnapping in 1983 of a Basque businessman in France, Barrionuevo managed, as did Vera, to avoid serving more than a token sentence. The businessman, Segundo Marey, had turned out to be a French citizen with no connection to ETA and was released after being held blindfolded for ten days (during which time the Spanish police debated whether or not to simply kill him in order to avoid public embarrassment). This type of screw-up is what happens when you rely on the likes of Lyndon LaRouche to help construct your hit list.

According to plan?

Basque lawyer Iñigo Iruin gave an speech on the GAL in the town of Tolosa in 1996 where he described French involvement that fits perfectly with the contacts that Quinde is reported to have set up:

«…we could now say that the French police took part directly and actively prior to the attacks being committed. They took care of certain missions, such as the collection of information and identifying targets. They collaborated with members of the Spanish Police, delivering documents with photos of [Basque] refugees who had applied for residency permits in the North [the French Basque Country], and also took care of getting photographs for them from the police archives.

«They paid them with funds reserved for the Ministry of Interior. In the court summary for Lasa and Zabala, it appears in the summary of relevant data on these tasks of cooperation. As a result we could say that the documents and information that were obtained as a result of the collaboration between the two police forces got to the Civil Governor, and that this is what the CESID [Centro Superior de Información de la Defensa–Spain’s military intelligence agency] transmitted via coordination with the provincial committee. They also sent a copy to the Headquarters in Intxaurrondo [headquarters of the Spanish Guardia Civil’s GAL activities].

«When Madrid received the information, they took the facts into account and decided on the desirability of whether or not to carry out the actions. It also demonstrates behavior that we saw in the previous times, and that is the passivity [of the police] after the completion of the attacks in order to facilitate the escape of the mercenaries, voluntarily delaying police roadblocks and their placement, or taking other measures.»

Justice denied

Manuel Ballesteros died in January 2008 of a heart attack. He never spent a single day in prison for his participation in torture or for covering up various murders, despite the fact that some of his subordinates and superiors were found guilty and served at least token sentences. Spain’s leading newspaper, El País, in its obituary on Ballesteros, sanitized his abysmal human rights record and described him simply as an «antiterrorist expert.»

Two years after Ballesteros’ death, Herbert Quinde–who had ceased to be a full-time LaRouche aide by the mid-1990s but remained in the organization’s orbit well into the 2000s via Pacific Tech Bridge, a strategic political and business advisory company which he ran with LaRouche security aide Paul Goldstein–was named chief information officer of the Illinois Department of Corrections. He was hired in part because of a letter that Admiral Bobby Ray Inman, the former head of the National Security Agency and former Deputy Director of the CIA,[FN 10] sent to Jerry Stermer, Democratic Governor Pat Quinn’s chief of staff, praising Quinde for his «deep interest in social justice.»

Quinde has never been questioned by Spanish prosecutors about his role in facilitating the «dirty war» against the ETA.

SIDEBAR

José Barrionuevo meets the LaRouchians

By Dennis King and Darrin Wood

The month following the meeting where Quinde and his French companion turned over the addresses, photos, etc. of ETA members living in France, Spanish Interior Minister José Barrionuevo–the man ultimately responsible to Prime Minister Felipe González for carrying out the government’s counterterror policy against ETA–granted an interview with three persons described as «EIR correspondents.»

The three who met with Barrioneuvo on April 19, 1983 were Anno Hellenbroich, head of LaRouche’s intelligence operations in Europe; his wife Elisabeth, an EIR staffer; and Katharine Kanter, also an EIR staffer (both Ms. Kanter and Ms. Hellenbroich had previously covered Spain’s terrorism problem for EIR).

EIR’s introduction to the interview, which was not published until June 21, praised Barrionuevo for taking a hard line against ETA, noting how he’d «opposed measures such as the proposed British-style habeas corpus law that would inhibit the questioning of detainees.» Since the editors inserted into the next paragraph a passage supportive of the notorious torturer Ballesteros, one could easily infer that EIR’s opposition to habeas corpus was motivated by a concern that it might inhibit the use of torture by Spanish counterterror forces.

The passage in question criticized Spain’s Ministry of Justice (although, curiously, an interview with Justice Minister Joaquín Ledesma by the three «correspondents» was printed in the same EIR issue) for «forc[ing] Manuel Ballesteros, the former head of the Joint Counterterror Command, to testify to the French government» about the 1980 Bar Hendayais attack. (As described in the main article above, this was the case in which Spanish death squadists attacked a Basque bar in France, killed two persons with no known connections to ETA, and then fled back into Spain. The Guardia Civil briefly apprehended the three but then let them go pursuant to instructions from Ballesteros, who would subsequently protect their identities through thick and thin.)

The questions posed to Barrionuevo by the EIR interviewers appear to have been crafted to get him to commit himself publicly to a hard line, but as a politician he managed to wrap his replies in Socialist Party hypocrisy. He stated that terrorism in the Basque region must be opposed aggressively to prevent «the most reactionary sectors of the country, who think that the democratic system is too weak to fight this kind of criminal activity» from gaining new influence. In hindsite (knowing what was later revealed about the GAL), it is clear that Barrionuevo was saying in effect that Spain must use Franco’s methods against ETA or else the «enemies of democracy» (Francoism) would use the Basque group’s terror attacks as an excuse to stage a comeback. His argument ignored the number one cause of the neo-Francoist threat, which was not the activities of the ETA but the failure of the politicians of the new democracy to purge the old crowd from the security establishment and to take strong action to transform the lawless subculture of the nation’s police.[FN 11]

The LaRouchians then put forward their theory that the war on ETA should be regarded as part of Ronald Reagan’s international war on drugs (the same line they would push re Central America in an effort to enhance U.S. support for death squads there), but Barrionuevo stated, flatly: «We have no evidence that the drug problem in our country is related to the terrorist problem.»

The LaRouchians, apparently trying to give the impression that they were back-channel diplomats for the United States, then asked:

«Any intensification of terrorism in Spain represents a danger of destabilization. In your opinion, is the White House sufficiently motivated and informed on this danger? What more would you like, regarding international cooperation, from President Reagan?»

And Barrionuevo, dropping for a moment his posture of cautiousness, replied: «We would like it if the U.S. government were more active, like the unique case of the French government…» (Emphasis added.) This could be interpreted as referring, among other things, to the information (photos and addresses of Basque refugees in France) provided by Quinde’s French Gendarmerie companion during the meeting at the Puerto del Sol antiterrorist headquarters the previous month.

The LaRouchians clearly had succeeded in making themselves useful to Spanish anti-terrorist officials, but who were they really working for? Or to be more precise: How did this group of amateurs get inserted into an operation of such unusual sensitivity: French security officials providing intel to their Spanish counterparts so the latter could send killers across the border into France to kidnap or assassinate people who in some cases were French nationals?

On Jan. 21, 1983, LaRouche visited CIA headquarters in Langley, VA where he met with the Director of European Analysis. According to a memo summarizing the meeting that was sent to John N. McMahon, the agency’s deputy director (full text here), LaRouche did not make a good impression, harping on conspiracy theories rather than providing hard information. However, one thing he said turned out to have a nugget of truth:

«[Mr. LaRouche’s] concern about terrorism, drugs, and guns ‘intersects with’ his concern about instability. He is trying to organize ‘an institutional structure’ here, in Europe, and in other developed countries to ‘counteract catastrophe.’ To this end, he has set up contacts with many officials who share his concern–particularly in France, Italy, and Spain–and often serves as a ‘catalyst in the anti-terrorist field.’ Mr. LaRouche clearly views France as an island of relative stability, because of the strength of its institutions. He claims to have sympathetic contacts (collaborators?) throughout the French government and ‘extending right into the Presidential Palace.’ In Spain, his contacts are mostly with the ‘old crowd,’ but he believes the new crowd can be worked with as well. (Gonzalez may be ‘salvageable’ if he and his Socialists can be ‘broken from Brandt et al.’)» (Emphasis added.)

We can see from the investigative articles and books on GAL published over the years, and from the backfiles of LaRouche’s EIR from the early and mid 1980s, that the LaRouchians did indeed have, or were in the process of developing, important ties with Spain’s «old crowd» (the neo-Francoists) and that the Socialist government did prove «salvageable» on the terrorism issue from both the LaRouchian and the old crowd viewpoints. We can also see that LaRouche and his followers had important contacts in the French government (else why would a top aide to the head of the Gendarmeries be working with Quinde?). Indeed, in 1984 the LaRouchians would disclose a classified Franch cabinet memo which they believed had smeared them (by suggesting they were working with the KGB). The disclosure created a minor flap over government security since the memo had been distributed to fewer than a dozen top French officials and whoever leaked it probably enjoyed access to a wide range of government secrets.

A German connection to GAL?

One country was missing from the list LaRouche provided to the CIA of the European nations he was supposedly working with on counterterror issues–West Germany. This is curious because LaRouche’s European intelligence headquarters were in Wiesbaden and his organization had been churning out reports about the threat of terrorism which were aimed at, and assiduously distributed to, West German security and intelligence officials. The omission was also curious because West Germany was facing a significant internal problem from groups such as the Red Army Faction and the Revolutionary Cells, which, although they lacked the popular support enjoyed by ETA in the Basque region of Spain, certainly represented a greater terrorist threat than existed in France–and were comparable to Italy’s Red Brigades in their capacity to stir up public anxiety.

According to the CIA memo on the meeting with LaRouche, he showed no fondness for top German leaders, calling Germany’s then Chancellor Helmut Kohl «stupid» and saying that former Chancellor Helmut Schmidt had «traded his strategic interests for a deal with his Bohemian Grove friends.» But disagreement with the leaders of a country has never stopped the LaRouche organization from seeking out «factions» within that country’s government who might be open to some of LaRouche’s views and suggestions (for instance, while Jimmy Carter, whom LaRouche hated, was president of the United States, members of the LaRouche organization sought out military and intelligence officers, especially retired ones, and tried to interest them in a joint campaign to save America). Furthermore, the LaRouchians who were assigned to the task of cultivating contacts within government bureaucracies during the 1980s generally were better informed on the relevant issues, socially more adept, and seemingly more rational than LaRouche himself.

Could the LaRouchian role in the formation of GAL have had any connection to the German government? Herbert Quinde, the main LaRouchian player in Spain at that time, operated out of LaRouche’s private intelligence/EIR offices in Wiesbaden, where Anno Hellenbroich, who would meet with Barrionuevo on behalf of EIR, was the leading figure. And Anno Hellenbroich just happened to be the younger brother of Heribert Hellenbroich, who, as of 1983, was the director of the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, or BfV, West Germany’s domestic intelligence service, responsible among other things for combatting terrorism.

Anno Hellenbroich.

The elder brother had joined the BfV in 1966, became its vice president in 1981 and then served as its president from 1983 to 1985 before becoming briefly the head of the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), the West German foreign Intelligence service. According to ex-members of the LaRouche organization, he was an occasional friendly visitor to LaRouchian events.

Heribert Hellenbroich.

Heribert Hellenbroich had managed to remove the LaRouche organization from the BfV’s watch list of extremist organizations on grounds that it did not display «excessive nationalism.» And during the early and mid-1980s LaRouche followers based in Wiesbaden undertook projects that seemed to be geared towards pleasing West Germany police and intelligence agencies. These efforts included gathering information on terrorism, as noted above, but also included

* the preparation of reports and dossiers on the Green Party, the peace movement and various nonviolent leftist groups (the LaRouchians advised that they be treated as part of a terrorist support network and thus be harshly repressed);

* political agitation about the threat of a Soviet invasion (expressed in alarmist language) and for large increases in the West German military budget (as for the development of superweapons); and

* a COINTELPRO-style harassment campaign against Green Party leader and anti-nuclear weapons activist Petra Kelly that included sexual smears (like the broadside «Have You Seen This Whore on Television?»), threats and stalking, and which was aimed at causing her to have a nervous breakdown.

Petra Kelly, 1947-1992. She retained former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark to represent her in a New York lawsuit in 1983 aimed at stopping the harassment. According to Clark, «they cornered her on a train, they shoved her grandmother around…They abused her most fundamental rights of privacy, dignity, physical integrity, and reputation.»

It was as if LaRouche’s operation in Wiesbaden was striving to be (if indeed it had not actually become) a clandestine branch of the West German government’s Cold War apparatus. And the channels of communication were not just based on the relationship of the two Hellenbroich brothers. The LaRouchians’ overtures to West German intelligence date back to the early 1970s, when they cadged a meeting with retired spy chief Reinhard Gehlen, who, after serving as the head of Wehrmacht intelligence on the Eastern Front in World War Two, had played the central role in building up the pro-Western intelligence organization in occupied German that would evolve into the BND (Gehlen served from 1956-1968 as the director of the BND–the same position that Heribert Hellenbroich would occupy briefly in 1985).

Gehlen was distrustful of the LaRouchians because of their still nominally leftist politics, but after they decisively moved to the right and built up their own private intelligence capabilities they began to attract serious attention, according to Brig. Gen. Paul-Albert Scherer, a chief of German military counterintelligence in the 1970s who became a strong LaRouche supporter after his retirement.

In a 1987 statement submitted to a LaRouche-sponsored factfinding commission, Scherer claimed that, as early as the 1970s, «experts were amazed at [LaRouche’s] connections and his access to special information on terrorism, the drug scene, the intelligence services themselves, and on the details of developments in the Eastern bloc countries and in the Middle East.» Scherer also stated that when presented with the opportunity, as a private citizen, of cooperating with the LaRouchians, he decided, in keeping with his «duties as a bearer of state secrets» to check them out.

«I asked around to friendly intelligence services and in political circles, before I took up any direct contact with the LaRouches [he means Lyndon and Helga LaRouche]. The fact that I did take it up, and can speak publicly about it here, says enough…»

Brig. Gen. Paul-Albert Scherer, former chief of West German military counterintelligence.

Over the years since then, the LaRouche organization has seemed to lead a charmed life in Germany. Although relentless in producing and distributing anti-Semitic propaganda of a slyly insidious character, it remains off the list of right-wing and left-wing extremist organizations that are included in the BfV’s annual reports. Although it has a reputation for deceptive recruitment methods and for using brutal «ego-stripping» indoctrination tactics on young people, it has never been the target of the kinds of pressure that the German government has exerted against another alleged cult, the Church of Scientology. (The profile of Scientology in the 2008 BfV annual report describes traits almost identical to those of the LaRouche organization, including the maintenance of an international private intelligence apparatus, the development in Germany of a politicized youth movement, and the supposed advocacy of totalitarian political goals. However, the BfV does not classify Scientology as an anti-Semitic hate group, which speaks volumes as to the German government’s double-standard see-no-evil approach to LaRouche’s band of Jew haters.)

Although LaRouche is a convicted felon who was sentenced in 1989 to 15 years in U.S. federal prison for running a giant loan fraud ring (he was let out on parole in 1994), he is allowed to visit Germany whenever he likes to spread his message of hate and facilitate the brainwashing of young people from all over Europe at his organization’s Wiesbaden headquarters. And although the German authorities have complained to the United States about the fact that U.S. neo-Nazi groups print propaganda materials for their comrades in Germany, there have been no such complaints about the fact that the U.S. LaRouche organization has subsidized its German branch and the latter’s propaganda materials for almost 40 years.

But most telling is the German government’s ignoring of information that came out in the U.S. media in 1984–that LaRouche, while visiting Wiesbaden in 1977, had raised the idea with top aides of killing President Carter, NATO Secretary-General Joseph Luns, and other dignitaries by use of remote-controlled radio bombs. This was reported on NBC-TV’s «Nightly News» in 1984, in a segment that also included the fact-finding director of the Anti-Defamation League calling LaRouche a «small-time Hitler.» LaRouche claimed that he’d been libeled by NBC and the ADL, and sued them in federal court; but a jury of his peers determined, in the fall of 1984, that the statements were NOT libelous–indeed, the jury was so repulsed by LaRouche’s display of paranoia and hate on the witness stand that they awarded NBC $3 million in punitive damages on a counterclaim (later reduced by the judge to $200,000).

The German security and intelligence services, including Hellenbroich’s BfV, surely knew about the NBC allegations. The LaRouche v. NBC trial was one of the most intensely covered civil trials in the United States that year; for instance, the Washington Post wrote a three-part investigative series on LaRouche shortly afterwards, as well as providing direct coverage of the trial itself. And EIR, which was widely circulated in German security circles, also reported on the trial in its own inimitable fashion. However, none of this was sufficient to get the LaRouchians restored to the BfV watch list.

A murder 20 years later

More evidence of how well-protected the LaRouche org has been, was revealed eight years ago when a Jewish university student named Jeremiah Duggan–a U.K citizen studying in Paris– died under mysterious circumstances while attending high-pressure indoctrination sessions at the headquarters of EIR in Wiesbaden, where Anno and Elisabeth Hellenbroich were still working. Jeremiah ended up dead on a highway near the EIR offices shortly after dawn on March 27, 2003. Within hours, the police were claiming it was a suicide. They said he’d deliberately run into highway traffic near the EIR offices–they never considered the possibility that he’d been running away from someone.

The LaRouchians weren’t going to be any help in getting to the bottom of this. They held a meeting at the EIR offices only hours after Jeremiah’s death, with Elisabeth Hellenbroich present, where members were ordered not to talk to anyone–not even to each other–about the death of this young man, who was now described as an «enemy» and a «spy» (in fact, he’d expressed his disagreement with their anti-Semitism at one of the indoctrination sessions and had made plans to return to his studies in Paris). Meanwhile, leaders of the LaRouche organization buttressed the suicide theory by telling the police that Jeremiah was a mental patient and was on psychiatric medication–allegations that were shown to be false at a UK coroner’s inquest later that year.

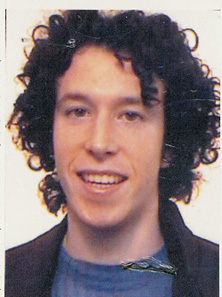

Jeremiah Duggan, 1980- 2003. He stood up in a LaRouche cult brainwashing session to protest the rampant anti-Semitism, proclaiming «But I’m a Jew!» That may have sealed his fate.

The behavior of the police was as suspicious as the circumstances surrounding Jeremiah’s death. In making their determination of suicide they assumed things about Jeremiah’s state of mind that only a mind reader could have known. They failed to perform an autopsy (in defiance of the recommendation of a medical officer at the death site), failed to take witness statements from the motorists whose cars may (or may not) have struck Jeremiah, destroyed his clothing without the parents’ permission (and without conducting any forensic tests on the clothes), failed to investigate–or to show more than a cursory interest in–what happened to him during the hours before his death (and hence failed to treat the EIR offices as a possible crime scene), accepted at face value the defamatory things the LaRouchians said about Jeremiah, and, when his parents arrived from London, told them that LaRouche’s Schiller Institute was a «respected» local organization.

In the years since, Jeremiah’s family has gathered witness statements and other evidence suggesting that he was in the EIR offices only minutes before the purported time of his death, and was beaten, chased, «hunted down.» The family hired forensic experts to examine the remaining forensic evidence (mostly photographs of his corpse and of the cars that supposedly struck him); these experts determined that he had wounds consistent with a beating, not with being struck by a car, and two of the experts expressed the opinion that the highway accident may have been staged. The evidence was sufficiently strong to persuade Baroness Scotland, the UK Attorney General, to take in 2010 the extremely rare step of ordering a new inquest.

Yet the criminal justice system in Germany still refuses to perform a proper investigation; has used Wiesbaden’s daily newspaper to portray Erica Duggan, Jeremiah’s mother, as obsessed; and has failed to disassociate itself from LaRouchian propaganda attacks on Ms. Duggan and her supporters that are crafted to give the impression that the German authorities agree with the LaRouchians.

A Hessen prosecutor in Wiesbaden, Hartmut Ferse, played an important role in this coverup during the mid-2000s, strongly defending the police determination of suicide and opposing any and all attempts to treat the case as a possible homicide. Ferse formerly had been the director of the Hessen state office for Defense of the Constitution (also located in Wiesbaden), which is the counterpart on the state level of the BfV. In other words, he had been engaged (among other things) in counterterror investigations in the same city where LaRouche’s terrorism-obsessed EIR had its headquarters and from whence the LaRouchians were eagerly cultivating counterterror officials throughout Germany.

If indeed the LaRouchians have had a long relationship with German security and intelligence services, and if they have had similar relationships with comparable agencies among Germany’s allies, and if in fact they were sometimes deployed as a deniable arm’s-length instrument during the Cold War to engage in a variety of questionable activities, then strong motives would exist, even today, to keep them out of trouble.

If a homicide investigation of Jeremiah Duggan’s death were announced and then pursued vigorously, it might begin to bear fruit, even after eight years, since the names of several of the young thugs who were probably with him in the EIR offices in the hours before his death are known. The case has a potential for attracting major attention from the media in Germany, in the UK, and in France (where the attempts to recruit Jeremiah began under the direction of Jacques Cheminade, the former French foreign ministry official who heads the French LaRouche organization). And enterprising journalists might begin to probe the LaRouche organization’s history of contacts with the BfV, the MAD, the BND–and the Bundeskriminalamt, or BKA (the Federal Criminal Police Bureau), which has its national headquarters in Wiesbaden, has used LaRouche’s local printing company as one of its vendors, and has discouraged Scotland Yard from looking into Jeremiah’s death.

One can only imagine the public’s response if it were revealed that the German security and intelligence services had acquiesced in the cult brainwashing of young German citizens for reasons of state. And that the BfV had deliberately turned a blind eye even after LaRouche began to organize these youth into the suggestively named «LaRouche Jugend.» And that LaRouche’s Wiesbaden-based intelligence operation may have been working for, or encouraged by, elements of the German government when it hounded Petra Kelly and helped to set up death squads in Spain, and while it conducted a relentless decade-long hate campaign against Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme (he was assassinated in 1986 and the murder has never been solved; to this day, however, the most plausible theory is that the shooter was Victor Gunnarsson, a former member of the Swedish LaRouche movement).

No one in the intelligence community in Europe wants to stir this hornet’s nest, which has the potential to strongly embarrass the spy agencies of France, Italy, Sweden and the United States, as well as the BfV and other German agencies, and may involve activities, especially during the late Cold War years, about which the public at this point has no clue. But the documented involvement of the Wiesbaden LaRouche staff in facilitating the GAL death squads may be the thread that, if followed further, will begin to unravel the entire skein, including the truth about the quashing of a murder investigation 20 years later.–DK

————————————-

Some of the footnotes below are by Darrin Wood; others were prepared by Dennis King based on research by, and interviews with, Mr. Wood.

[1] Those who organized the GAL campaign apparently didn’t care very much if innocents were killed as long as the desired objectives were achieved: to prevent ETA members and supporters from walking the streets of southern France without fear; and to pressure the French government into cooperating with Spain’s counterterrorist program. The upshot was that at least a third of the people killed, and several more who were wounded and kidnapped, had no known connection to ETA. A list of the GAL’s attacks and of the high-level police and Justice Ministry officials who were ultimately convicted for these dirty-war crimes can be found at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grupos_Antiterroristas_de_Liberaci%C3%B3n (last accessed, Sept. 13, 2011).

When Conesa died in 1994, the Spanish daily El País described him as «one of the leading protagonists of police repression» and noted how he’d «dealt harshly with leftist intellectuals and workers….Many still remember the terrible interrogations they underwent [at the hands of] Conesa…» The obituary also revealed that Conesa had worked in the Dominican Republic with the police of the dictator Rafael Trujillo (a psychopath who routinely used tortures of the most horrific kind to keep the people of his country from expressing any discontent).

Getting off on torture: Roberto Conesa.

Conesa served as Ballesteros’ mentor, the man with whom Ballesteros would collaborate for so many years. And it should be noted that Conesa began his career in a manner remarkably similar to the LaRouchians–as a youthful former leftist who informed on his erstwhile comrades to Franco’s secret police and then discovered that he really loved making people suffer.

For more details on Roberto Conesa and Spain’s state terror bureaucracy, see «The Spanish police transition: a paradigm of continuity,» by Mikel Aramendi, Statewatch Bulletin, vol. 19, no. 2, April-June 2009; http://database.statewatch.org/article.asp?aid=28993 (last accessed, Sept. 13, 2011).

[3] The information about the killing of the gypsy child and her sister is from Paddy Woodworth’s Dirty War, Clean Hands: ETA, the GAL and Spanish Democracy, Second Ed., Yale University Press, 2002, p. 54. A list of some of the other BVE victims, with descriptions that identify the ones who had no known connection to ETA, is provided at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Batall%C3%B3n_Vasco_Espa%C3%B1ol (last accessed, Sept. 13, 2011). Although most of the murders took place in or near the Basque Country, there were two in Paris and two more in Caracas, Venezuela, suggesting a chilling (if small-scale) parallel between the BVE and Operation Condor–the infamous cross-border campaign by Chilean, Argentinian and other Southern Cone secret police agencies which resulted in the deaths (from the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s) of tens of thousands of left-wing refugees who had fled their respective countries.

In the 1990s, the LaRouche organization began to churn out articles accusing the ETA and the Basque diaspora in Latin America of being part of a British-Jesuit-Rothschild controlled narcoterrorist conspiracy to annihilate the armed forces and nations of Mexico, Venezuela, Brazil and other countries. The intent of such propaganda–and the fantasies behind the intent–should be obvious.

The author’s need to rationalize his organization’s dealings with the unreconstructed Francoist elements in Spain led him to produce what essentially was hate propaganda against both the Jesuits and the Basque people, depicting the former as Satanists and the latter as the inheritors of an evil Jesuit-fostered culture addicted to witchcraft. (Herbert Quinde appears to have picked up on this theme in a speech he gave to a LaRouchian conference in January 1986, when the GAL death squads he helped to set in motion were still active in Spain and southern France: «It may be time,» he stated, «to start burning witches again.»)

[5] In a March 1, 1983 article, LaRouche’s EIR described the Bar Hendayais attack as a «shootout between Spanish Police and ETA on French soil»: an odd description given that only one side did any shooting. And it’s significant that the LaRouche magazine would describe the two gunmen as Spanish cops even though neither of them was ever officially identified as such.

The Azules actually existed as a rightist faction within the ruling UCD. Rosón was a member and so was Martín Villa, who had held several important government posts during the final decade of Franco’s rule. While serving as the UCD Interior Minister, Martín Villa became known as the «hammer of the Transition» because of his harsh crackdown on demonstrations by students and workers, and he allowed the BVE death squads to operate with impunity.

Martín Villa (center) gives fascist salute in 1974.

In the case of Antonio Ibáñez Freire, who served as Interior Minister from 1979-80 (in between Martín Villa and Rosón), and died in 2003, we have an Azul of a different type: a veteran of the Legión Azul, the notorious «Blue Division» of Spanish volunteers (the majority of them fanatical Falangists), who served under the Nazis on the Eastern Front during World War Two. Like his predecessor and successor at the Interior Ministry, Ibáñez Freire–a recipient of Hitler’s Iron Cross–staunchly supported the BVE death squads.

EIR’s currying favor with the Azules and Rosón circa 1982 suggests that the LaRouche organization’s secret lobbying in Madrid for a new cross-border offensive against ETA began long before the known meetings between Quinde, LaRouche, the French Gendarmerie officer and various Spanish security officials. What is known so far may just be the surface of the iceberg, especially if the LaRouche organization’s contacts in the German and U.S. intelligence communities–and the details of how Quinde connected up with French security officials–are taken into consideration.

[7] It is widely believed that Waffen-SS Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny (1908-1975) headed the ODESSA network that helped Nazi war criminals flee to Latin America and hide there under new identities. Supposedly, ODESSA (which really did exist on some level) was financed by «Nazi gold» that the Allies had failed to seize at the end of the war. Author Dennis King has commented elsewhere on this website about Quinde’s curious request for information on the finances of the Skorzeny family, suggesting that Quinde’s boss LaRouche regarded himself as «the proper heir» to the «rumored Nazi nest egg.»

After extended torture the young men were in such bad shape they could not be simply taken to a hospital without the danger of a replay of the Arregui case. So they were stuffed into a car trunk and driven 800 kilometers to a remote site in the province of Alicante, where they were shot (reportedly after being forced to dig their own graves). Their remains were found in 1985 but were not identified until ten years later, because they’d been buried in quicklime.

In the 1990s, five individuals were convicted in the Lasa and Zabala case. Two agents of the Guardia Civil, Felipe Bayo Leal and Enrique Dorado Villalobos, were each sentenced to 71 years in prison. Lt. Col. Angel Vaquero, also of the Guardia Civil, was sentenced to 73 years in prison. General Enrique Rodríguez Galindo, commander of the Guardia Civil’s most important base in the Basque Country–at Intxaurrondo–was sentenced to 75 years in prison, as was the Socialist Party’s Civil Governor in the province of Guipúzcoa at the time, Julen Elgorriaga.

The total sentences for the five felons added up to 365 years, but what actually happened? Elgorriaga was released from prison–due to «reasons of health»–after spending only one year behind bars for the kidnapping, torture and murder of Lasa and Zabala. Gen. Galindo received the same treatment three years later. Felipe Bayo Leal, Enrique Dorado Villalobos and Lt. Col. Angel Vaquero quickly received a change in their imprisonment by being granted Spain’s «Third Grade» status, meaning that they only have to spend nights in prison and can get frequent passes for longer stays at home.

It is interesting that Rodríguez Galindo was promoted to General of the Guardia Civil at the same time that his involvement in the Lasa and Zabala case was becoming known.

[9] Unfortunately, the conservative Popular Party, which took advantage of the GAL scandal to win the 1996 election, would itself step up the repression in the Basque Country. The police under the PP targeted not only ETA combatants but also people perceived as being sympathetic to the ETA’s goals, and continued the use of torture on a large scale. The police banned many noncombatant organizations (which were defined as pro-ETA according to very elastic standards), closed newspapers and even outlawed the posting of pictures of ETA political prisoners in the Basque Country’s many bars. This was pretty much the strategy that the LaRouchians had urged in 1983 as a supplement to counterterror violence.

The human rights abuses in Spain against ETA fighters and non-combatant sympathizers have continued into the 21st century. In February 2004, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Theo van Boven, issued a report on a visit he’d made to Spain the previous October. According to a summary published by Statewatch, the report included

«allegations that torture was practiced ‘more than sporadically’ by State security and police forces, and that safeguards and the investigation of torture allegations were ‘ineffective.'»

Van Boven also reported on how Basque victims of torture were placed in a double bind–if they accused the police of having tortured them, the very accusation was sometimes cited as «proof» that they were ETA supporters (because the ETA had allegedly compiled «instructions for filing torture allegations»). The Rapporteur cited a case involving journalists who are colleagues and friends of Darrin Wood:

«In the case of Martxelo Otamendi, editor of the Egunkaria Basque-language newspaper which was shut down [and] accused of being financed and directed by ETA in February 2003, his claims that he (and other colleagues) were tortured during incommunicado detention resulted in additional charges being filed against him by the government in March 2003, accusing him of ‘collaborating with an armed band’ by making torture allegations to discredit the institutions.»

Newspaper editor Martxelo Otamendi: first he was tortured, then he was denied legal redress by a «Catch 22» legal system. And, oh yes, the Spanish state shut down his daily newspaper, Euskaldunon Egunkaria, for seven years. This crackdown was not because Egunkaria was ETA affiliated (it wasn’t–Otamendi opposed the ETA’s use of terror tactics) but simply because it published an interview with an ETA leader, promoted the use of the Basque tongue and had nationalistic leanings. Essentially democratic Spain was treating the Basque region as if it were an occupied foreign country. In 2010, a unanimous decision by the Criminal Court of the Audiencia Nacional (the high court in Madrid) finally established that there had never been any grounds for closing the paper and that «the allegations have not been proven that the accused have the slightest relation with ETA.» (Read profiles here of six journalists and scholars from the Egunkaria staff who were imprisoned.)

The Spanish government replied to Van Boven’s report by saying that the allegations of torture cited by him were impossible to verify, that airing them would jeopardize the lives of police officers, and that the human rights organizations that monitor torture complaints are themselves part of the terrorist support network (the latter point is a staple of LaRouchian propaganda, which often includes suggestions that the secret police and military of various countries should crack down on human rights workers).

Read the full summary of the Rapporteur’s report at http://www.statewatch.org/analyses/no-39-un-torture.pdf (last accessed, Sept. 20, 2011). And don’t think the situation has improved since 2003; read Amnesty International’s 2009 report on torture in Spain at http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/EUR41/004/2009/en/d8b50781-9226-4841-b05d-8adc33e5f94c/eur410042009en.html#2.Introduction|outline (last accessed, Sept. 20, 2011).

Admiral Bobby Ray Inman, former deputy director of the CIA.

Quinde often worked out of the LaRouche security office when he was not in Europe or Latin America. After 9/11, when he apparently was no longer active with the LaRouche organization’s covert activities, he ended up at Evolutionary Technologies Internationl (ETI), a company where Inman was chairman of the board. ETI produced counterterrorist tracking software for the CIA, the Department of Homeland Security and the Defense Department.

On the ETI web page, Quinde was described as having joined the firm in 2003 «as Director of Business Development where he successfully focused his activities on opening the U.S. Federal market to ETI Solution [ETI’s data integration software product] resulting in major engagements within the U.S. Department of Defense and the intelligence community.» The bio also claimed that Quinde had «over twenty years of experience» in, among other things, «organizational development» and «security consulting,» and described him as an «international affairs expert.»

For more more on the LaRouche organization’s relationship to Inman and many other individuals in the U.S. intelligence community, see Dennis King and Ronald Radosh, «The LaRouche Connection» in The New Republic, Nov. 19, 1984, and Dennis King’s Lyndon LaRouche and the New American Fascism (New York: Doubleday, 1989), especially Chapter 18.

http://lyndonlarouchewatch.org/Manuel_Ballesteros_and_LaRouche.htm